Articles by Pavel Kraus

How can you win customers for knowledge management (KM) projects?

Sometimes we get things right without thinking much about how we got there. For many years I have worked with and for middle and senior managers. The results were satisfactory, so I was recommended to their colleagues and received additional business from them.

It was only after the Corona years, when many of my colleagues who also worked in knowledge management consulting were struggling to get work, that I started to think about the success factors for my projects.

This has led in 2023 to the KMGN project for business-aligned knowledge management. In this project we defined the key success factors for KM. To give you an idea of our thinking, I will start by listing some of the objectives of my clients since 1998, when I received my first KM assignment, then as Knowledge Networking Officer for Roche Diagnostics.

Looking back and reflecting on these objectives, a pattern began to emerge. Here are some of my clients’ objectives that have led to well-paid KM projects:

- Managed a cross-functional IT project with the potential to save $120 million

- Enabled engineers to complete critical projects on time through efficient documentation practices

- Captured and transferred the knowledge of a high throughput programmer to meet agreed year-end targets

- Synchronized the collaboration of a drug development team to identify the most effective solution within the agreed timeframe to reach the next phase

- Developed a visual process collaboration portal to enable internationally dispersed teams to report financial results on time to meet regulatory legal requirements

These objectives have a common denominator. They are all objectives that executives negotiate with their line managers and, in most cases, their annual bonus depends on meeting them. And they are in line with the key objectives of their companies.

At that time I did not think any further about it, I just concentrated on the best KM methods to achieve these goals. Today, however, I recognize what I did not see at the time, that these are the success factors for winning a KM project.

A good rationale can be derived from this, namely that in order to win a KM project, you should start with the goals of the senior managers. As a rule, these goals are achieved most quickly with KM methods anyway. So you should communicate this to the managers from the start. This can be done best with storytelling.

That’s why we developed a «KM Storytelling Canvas» that outlines the story’s talking points in a way that creates an engaging narrative. This concludes our KMGN project, which involved knowledge managers and executives from Europe, the Americas and Asia.

Articles by Dr. Pavel Kraus published originally on Linkedin. Dr. Pavel Kraus is a consultant and university lecturer writing about knowledge management and associated themes. Read more articles by Dr. Pavel Kraus via the selection button below.

Thoughts on ETH Alumni “Knowledge Network” using a technological solution

The dream of a technologically supported knowledge exchange or knowledge network has existed since the 1990s. Starmind, the currently selected option, is one of a long line of software systems with this claim, e.g. Adarvo, Autonomy, Confluence, Finebrain, Humingbird, Livelink, Metalayer, Teampage. Starmind corresponds 1:1 to the former idea of Finebrain, Basel.

So far, however, only a few of these systems have met expectations and most no longer exist.

Depending on the company, there were various internal names for such systems. Yellow Pages at Novartis, Knowledge Organizer at Roche Diagnostics, Touchpoint at Roche Pharma, MedIS at Actelion or ReferencesPlus at Siemens.

These “Knowledge Network Systems” (KNS) offer at least the following functions:

- Static and/or dynamic creation of expert profiles

- Assignment of queries to experts based on rules and profiles

- Q&A archiving in a database

- Forwarding of queries on the basis of workflows

- Search tools for appropriate responses to queries

- Making documents created by experts accessible

The KNS software vendors make a number of assumptions that are often not fulfilled in organizations:

- Users can formulate their questions precisely and use the necessary technical terms so that the KNS can find suitable experts

- Experts pass on their knowledge to people they don’t know without worrying about IP (intellectual property)

- The experts create and complete their individual profiles on their own initiative and have the time to do so.

- Expert profiles can be created automatically, as there are many documents in which both the subject areas and the names of the experts appear. Their matching is unambiguous.

- The keywording of the expert knowledge in the expert profiles will later match the users’ search terms

- The breadth and depth of the users’ search queries across the specialist areas and the expertise stored in the expert profiles provide useful results.

- If not, users will have the stamina to keep searching

The work required to implement such a system is wide ranging. They can only be partially facilitated by AI. Here is a selection:

- Creation of a taxonomy or ontology for each area of expertise. This allows user queries to be placed in the right context.

- Ensure that this ontology is used for both the expert profiles and the user queries

- Funding an editorial team that can assess and manage the content and profiles from a discipline-specific perspective

- Clarifying the question of whether and how the experts are remunerated for their IP

- Creation of instructions and operation of a hotline for experts and users

Unfortunately, the same mistakes were repeated, as the effort involved was always underestimated and too little attention was paid to the work mentioned above. The focus was usually primarily on the technical IT implementation.

By the time they saw and understood all the effort required, it was usually too late to stop the project. One option was then to include simple, sometimes trivial content in the databases. Another option was to shut down the system quietly after a few months.

It is presently believed that AI will make it easier to set up these databases – quod esset demonstrandum.

It is difficult enough to introduce such a system in a company that can mandate its employees to participate. It is even more difficult in a voluntary organization like ETH Alumni.

Knowledge management back to square one – once again?

In discussions about what Knowledge Management (KM) is and what it encompasses, it sometimes seems to me that we are going around in circles and starting all over again. Dave Snowden said at Potsdam 2022 that those of us who have been in KM since the 1990s have seen the cycle of KM adoption and abandonment five times now.

Time and time again, the people who are trying to implement KM make exactly the same mistakes as those who have done it before, so that the executives no longer want to pay for it. Then it all goes away for three years, but then people still have to manage knowledge, so it starts all over again. But they repeat the same process and the same mistakes. As he said, we are now in the fifth cycle and we are going round and round again.

So what is the real problem?

Why does KM not evolve and learn from past mistakes? This should be one of the main components of KM – lessons learned.

Maybe it is the desire for quick and easy solutions. Or perhaps it is the love of tools and the hope that they will somehow magically solve the problem. I often start my KM workshops and presentations with the magic fairy. She comes and all KM problems are solved by themselves and everyone is happy. Unfortunately, we are still waiting for her.

3 ways how to start a KM initiative

There are three ways to start a KM initiative – two good and one bad. KM often starts in a support function, often in IT, quality management, or communications. After analyzing the nature of the organizational problem and KM, the initiative leaders realize the multifaceted nature of KM. In fact, many more functions are needed to support the initiative. Then they have three options:

1) Expand the initiative to include executives of other value creating functions such as research, development, production, sales, etc.

2) Stop the initiative because it is beyond your capabilities and other functions cannot be motivated to participate.

3) Implement some kind of tool, be it a database or search with or without AI.

The first two are the good ones and the last one – the most practiced – is the bad one. This is my personal experience, based on many observations.

KM Success Logic

In 2015 I wrote a chapter in the book «Wissensmanagement beflügelt»: How Knowledge Management Projects Fail Sustainably – On the Way to a Success Logic. There I summarized the experiences with KM implementations of the last 20 years.

The best option how to start a KM initiative

If KM initiative leaders choose the first option, they might consider the ideas in the above mentioned book chapter. In it, the first steps are to analyze the organizational strategy with its purpose and business model. How is value created? What are the key components for measuring performance and productivity?

With this in mind, a solution-neutral analysis is carried out as the next step. The key prerequisites for this analysis are both – a clear distinction between knowledge (tacit, implicit) and information (explicit knowledge) and furthermore a good understanding of the characteristics of knowledge as well as information quality. As a result of this analysis, key success factors for the organization are identified and addressed using the methods and techniques available in the KM toolkit.

Those knowledge managers who embrace this approach will break the vicious cycle of KM implementation failures. This is my hope and wish.

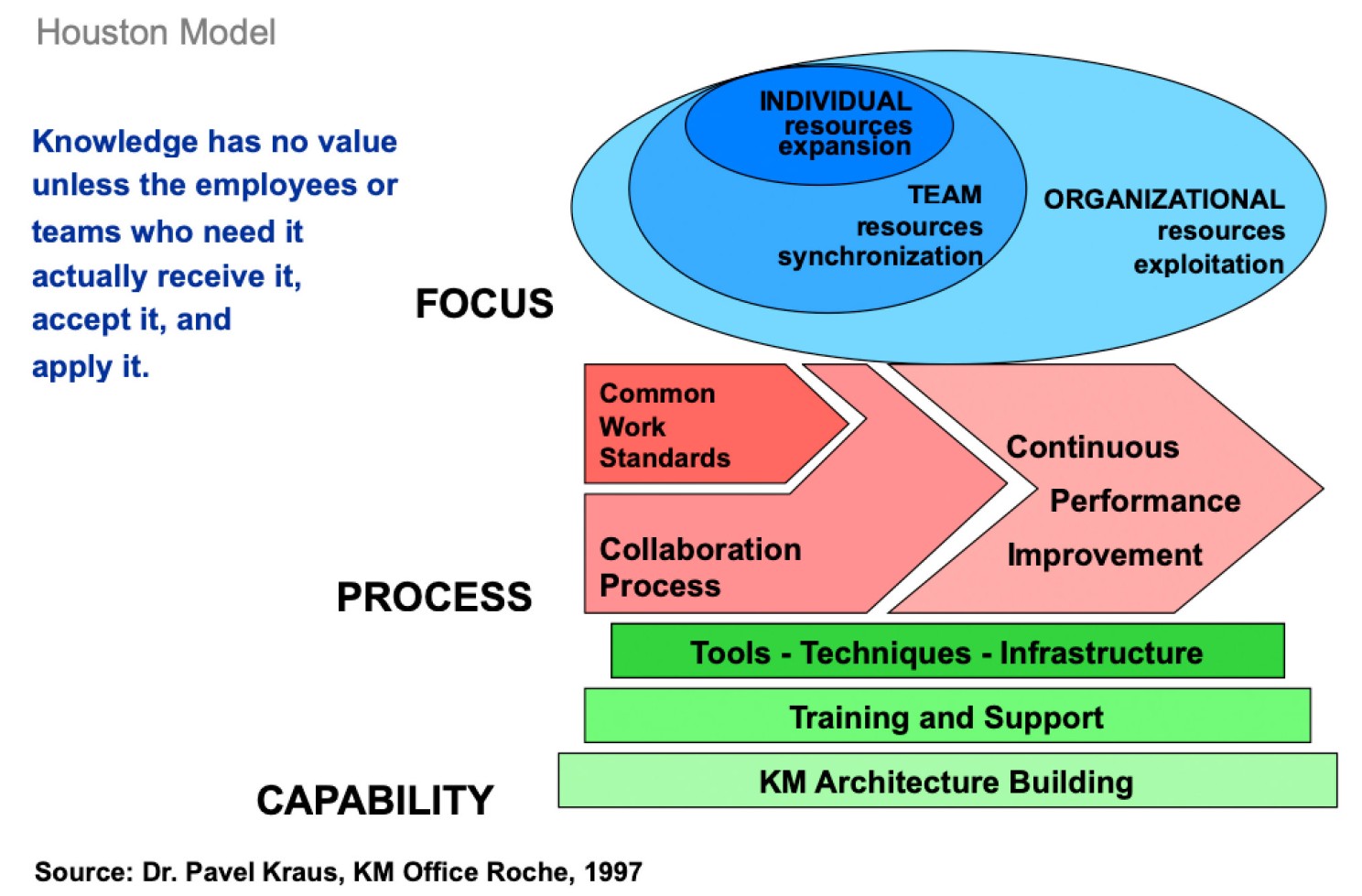

The Houston Knowledge Management Model: 27 Years of Impact

Those were the early days of Knowledge Management (KM). In the mid-90s, two colleagues from Roche Diagnostics and I attended a benchmarking conference on knowledge management. It was organized by APQC in Houston by Carla O’Dell and Cindy Hubert. Three full days were filled with presentations on various aspects of KM from more than a dozen organizations such as Siemens, Hewlett-Packard, World Bank, Xerox, Schlumberger. Speakers included people like Steve Denning, Josef Hofer-Alfeis, and many more.

During this three-day conference, we attended all the sessions and in our free time we gathered and tried to collect and analyze all the facets of KM that we saw.

It has been a great challenge to bring so many aspects, facets, and details into a framework in a way that they are mutually exclusive but collectively exhaustive. It also had to be as simple as possible. The goal was to quickly and clearly communicate to our management what KM is all about.

This culminated in the creation of a model that had three tiers: Focus, Process, and Capability. We called it the Houston Model because that was where the APQC conference was held.

This Houston model, now 27 years old, came to mind when I was recently asked by a student who had created a different three-tier model: People, Processes, and Tools. So I took the Houston model out of my drawer and reviewed it with the student. To my surprise, most of what was developed during those evenings at the Houston conference is still relevant today.

The Houston Model was the first of six that have been developed since, based on consulting work or discussions within the Swiss Knowledge Management Forum. The latest is a Problem-Consequence KM Story Model that is included in the 2024 Guideline ENABLING KNOWLEDGE MANAGERS TO COMMUNICATE BETTER WITH BUSINESS MANAGERS.

And here we come full circle. Once again, we are explaining KM and the value and importance of its place in the management toolbox.

The dilemma of a knowledge management consultant

Those were the early days of Knowledge Management (KM). In the mid-90s, two colleagues from Roche Diagnostics and I attended a benchmarking conference on knowledge management. The presentation was about implementing a KM system, basically a database designed to document employee knowledge and use it as a self-service portal. The same idea that we have heard and seen fail so many times since the early days of knowledge management in the 1990s.

But apparently there is still a strong hope that with the latest AI-assisted tools, it will work out one day. As I listened to this group giving their presentation, I couldn’t help but think of something my father once told me.

Mystery novels and Knowledge Management

He told me how he reads mystery novels. First he reads the end and only then starts with the beginning. Just to enjoy how painstakingly the detectives try to decipher the events and find the culprit. When he knows the ending, he enjoys the novel much more.

So at the student presentation, I felt like my father. I knew what was going to happen down the road. And I wondered why students were not using a fundamental KM tool, lessons learned. The failure of KM databases has been well documented for more than 25 years and any KM expert can attest to this if you were to ask them.

I realized that I could not counter their strong belief in the KM database and the promises of AI. As a KM consultant, I used to note in my calendar that I would return after one year in such a situation. Within that period, the KM database would have failed and people were ready to listen to better solutions. Sometimes they became my clients, in other cases they were fired or moved on to other things.

What would you have said to these eager and motivated students?

Is innovation in your business title?

Impressed by the recent proliferation of business titles that include innovation, I want to share in this short article my thoughts on what it takes to become an innovation manager. These are based on 30 years of experience in innovation management, either in practice, in consulting, or in teaching. This complements the textbook wisdom about innovation that is composed of creating a mutual vision, practicing psychological safety, management support, and striving for world class results.

Diving into a new industry

After five years in customer research in pharmaceuticals, I changed industries and started working in diagnostics. Our main customers have been heads of diagnostic laboratories and hospital CFO’s. Right after I was appointed the leader of a team of market researchers working with marketing and R&D folks, my boss sent me on a three month tour of hospital labs. My task was to deliver a detailed report on customer needs from various kinds of labs in the US, three European countries, and Japan.

I had to earn my place on the product team and gain recognition from the scientists and product developers, most of whom were highly experienced people with many years of experience in the industry. It was an exciting time to learn how different the work, organizational set-ups, and expectations in laboratories are around the globe. Even just across the border in Germany, the lab set-up and business models differ widely compared to France. In contrast, in the US manpower savings are key, while in Japan the customers look at the wrapping style of the gift you bring them.

Talking to customers

First-hand personal experience in the labs was the basis for understanding the way this industry ticks. All my visits to end customers were accompanied by sales representatives that gave me the necessary context to be able speak to the customers. Fortunately, talking to them the right way was not too difficult, as I had already learned how to talk to customers in my previous job.

When I started working in customer research right out of university, I received thorough training in interview and conversational techniques. My company had spent a lot of money training me in all the steps of customer survey projects. The first step was to understand the state-of-the-art technology, competitor landscape, and unmet customer needs from past research. The seconds step was to build a research design based on this knowledge, including discussion guides, talking cards, mock-ups and possibly even a simulation of workflows. Third was engaging personally with customers to find out what could be the next item on their need list.

The final step was to deliver this knowledge to the research and development folks using creative techniques so they could produce something that today would be called a MVP.

Transferring knowledge from customers to R&D

Often I would be watching focus groups behind a mirror wall together with product managers or developers to observe the first hand experience of our ideas. In both cases, it was hard work to be either present in the labs or to involve the relevant colleagues personally to go out there and get under the customer’s skin as we called it. Days and weeks of practice in front of individual customers or customer groups collaborating and dialoguing with them, or at least observing their daily work, going to the place of action or, as the Japanese call this practice, Genchi Gembutsu.

Another aspect of innovation management was to discover when real breakthroughs happen. In a consulting project I was asked to identify and describe the circumstances in which disruptive innovation occurred in the past. I was given the names of senior researchers who recently made a great discovery. In the interview I wanted to know when and where this happened, who was present, and what occurred a week, a day, and in the hours before. The goal of my client was to discover a pattern that could be broadly applied to innovation teams.

The moments of disruptive innovations

The findings were surprising in several respects. The key result was that there actually was a pattern. The discoveries did not happen during office hours, but in their spare time and often not on company premises. A few individuals from the larger innovation teams, usually three or four, went to discuss new ideas on their own initiative. While discussing, they draw their ideas together on a large sheet of paper placed between them. If computers were present, they were only used to check some data, if at all. So information was not necessary, the knowledge in their heads was all they needed. This became one of many innovations stories to be taught at the universities.

Three pillars to innovation

In summary, there are three pillars to my innovation experience. First is the thorough personal knowledge of the industry, the customers and their needs. Second is the mastery and practice of customer research techniques. Finally, a good knowledge of concrete cases from the history of innovation serves as a solid basis. For a start, get to know your Brown, Christensen, Deming, Drucker, Kotter, Probst, Ries, Senge, and a few others. Complement this with your own experience and creativity. Know many innovation stories by heart, either breakthrough, disruptive, or evolutionary cases.

For me, these pillars are the playing field to be mastered, so that you can go beyond them and find new creative solutions for customers.

The Three Levels of Knowledge Management

Since the dawn of knowledge management (KM) as a concept in the 1990’s, many people have associated it with some kind of database. The expectations have been high, the disillusionment accordingly high as well. Software companies have sold clueless customers «knowledge databases» with the promise to easily manage their knowledge.

Although this proved to be the wrong way, managing information is still an important part of knowledge management. When done correctly, it can improve process transparency, reduce redundancies and simplify processes. Thus, it can lay a good foundation for a KM framework. This groundwork I regard today as the first of the three levels of knowledge management.

Let’s assume there is already documented knowledge available. This explicit knowledge, or rather information, has to be processed and finally made available. It must be accessible to the right people at the right time, in the right quality and comprehensibility. In this way, it enables faster learning and the capacity for action.

How to excel at the first level?

We start with the information to be edited in such a way as to create sufficient depth for various audiences. This can be done by giving it structure through modularizing and visualizing. To cater to each target audience, one has to understand their needs. This means asking them what type of actions they carry out and what information they need to make that happen. Information can only be made relevant to the recipients, if you understand what decisions they take, who is involved and how much information is helpful in what form.

Once the right structure is there, the next process is dealing with the availability of the information.

Information overload has to be prevented. Recipients should get only as much information as they need at a given moment. We all know this process well from news website which offer two levels of information and detail; the first level, for example a headline and article summary, is readily available at the front of the site, while the second more detailed level only becomes visible when you choose to click on the «more information» button or something similar.

Information is only useful if it reaches the recipient in the right moment. Originally, it was thought that this would be done by a search carried out by the user. However, search, and especially full text search, has proven to be unsatisfactory. It overwhelmed the users, because they had to know the right keywords. Furthermore, it became increasingly difficult to know where to search, as the various document repositories and applications proliferated in the companies.

Then, the search results often returned complete documents in which the useful information was buried somewhere. This was especially the case when processing, structuring, and visualization were not performed to increase the quality of information.

How to provoke decisions and learning?

Recently, so called smart-search initiatives have tried to improve the contexts of searches. Metadata was given through controlled vocabularies and specific taxonomies. While this brought some improvements, the best access to information is still through the work context of the users. Work processes can be broken down to individual tasks. Navigating to these tasks automatically provides context. As a byproduct, this generates enough metadata for precise assessment of the information. The information can then be delivered quickly and precisely into the work situation, if structured as described above. The results are quick decisions and effective learning.

The second level of knowledge management

In the first level, we started with existing information. When looking at the second level, we have to take a step back. How do we arrive at the information in the first place? On this level knowledge management concerns itself with the knowledge in people’s heads.

Conversations and discussions during meetings or workshops can be of varied quality. What happens if the knowledge is present in the room, but it is not verbalized, or worse, is dismissed due to questionable arguments? Another way to lose valuable knowledge is when a blowhard is dominating the conversation.

So, in this level we focus on how knowledge flows in collaborative situations, but we should go beyond the classical meeting management and interaction rules. This means embracing facilitation and creativity techniques for normal team meetings like force field analysis, metaplanning, or the fish bowl.

The goal is to inspire the participants and give them opportunity to contribute their knowledge. Sometimes this has to be provoked. This works best if the context changes from time to time, as might happen in design thinking sprints. If the perspective suddenly changes, a new idea might emerge. If it is brought into the discussion, then by the power of association it can trigger further knowledge contributions from other participants and lead to innovative breakthroughs.

Workshop designs based on knowledge management principles work exactly like this. They are one of the prerequisites for state of the art innovation and project management. They use an orchestrated series of steps with changing techniques and perspectives. They use disruption to build on each other. That is the difference from the classical usage of serious games, creativity techniques, association matrixes and role-playing.

As in any context, leadership that provides an atmosphere of psychological security is the key to success. Without leaders who are equipped with this toolkit and have a deep understanding of the power of such an approach, you cannot get anywhere.

What comes beyond the second level?

Innovation endeavors, like design thinking, are usually limited to an existing framework of a company or industry. The question is how to break out of these limitations and embrace a truly holistic understanding of an issue. Something that really deserves the name of «thinking outside the box» and reverses the accustomed ways of thinking.

One way how to achieve this is first to compose a solution free perspective based on all the factors that might influence a path to the solution, especially those which are not yet recognized by the leaders in the field. Or, as Thomas Kuhn would put it, — create a paradigm shift.

The search for methods of how to explore possible solutions in a multi-dimensional, not yet quantified, highly complex problem field exist and have been developed by various thinkers like Donella Meadows, Fritz Zwicky, Jay Wright Forrester, Frederic Vester, Peter Senge, Dave Snowden and others. It is the world of interactions, interconnections, interdependencies, linkages, interweavings, networks, hierarchies or progressive differentiations. Various designations have been used for these methods, like morphology, systems thinking, systems dynamics, etc.

These methods reduce the complexity even when it seems non-reducible. First, the governing factors have to be identified. A broad understanding is needed. This has to come from a collaborative team covering broad fields of knowledge. Practically, this could mean that, for example, a health care problem is addressed not only by physicians, insurers, and policy makers, but also by social anthropologists, geographers, philosophers, and theologians. It means expanding the perspective on issues through true interdisciplinary collaboration. The toolkits for this exist already, one has only to tap into them.

The real quest is for identifying unknown governing factors that, when changed, have a profound effect on the solution. This is taking innovation towards a level that goes beyond what is currently known. Using these methods, we are in the position to re-invent industries and tackle human needs in completely new ways.

Today, we see scattered attempts to tackle this third level of knowledge management and I will explore this in another article in the future. The path to disruptive innovations is still to be discovered.

Frozen Knowledge

Knowledge has similarities with water. It also comes in three states: vapor, liquid and solid. And similar to knowledge the most productive and live-giving is the liquid state.

When thinking about knowledge, more and more we discover these similarities. We start with vapor. A notion, hunch or intuition comes first – before we can formulate an idea and tell it to others. This is like vapor that comes and goes and cannot be grasped.

However, as soon as we are able to pinpoint the idea and express the notion, it changes the state from vapor to liquid. It becomes tangible, it breathes and has life. Often it takes more than one person to develop it and to evolve it. But now our minds can start to work with it, explore it and discuss it with others.

Discussions and workshops are even more productive, when notes are taken, visualization techniques applied or serious games used. Ideally, they support the development of new ideas through associations and cross-pollination amongst the participants. This is true collaboration for innovations.

In this way the liquid knowledge is by and by transformed into solid state as we go on. If used properly a good mixture of knowledge (liquid) and information (solid) supports the knowledge flow and makes it more effective. Now we have reached what is the desired state. It is a powerful state in which context has been established, learnings achieved, actions and decisions taken, and new things discovered.

Later on, as the action has reached its goal and we have moved on, the information is left behind. Now the question becomes: Can knowledge be again generated from this captured information? From experience we all know, this really depends on the quality of that information. If the quality is high, one can quickly learn and re-create the knowledge in our heads again. If it is poor, then it takes much longer or it is hardly possible if at all.

In that case, the investment into the discussions, meetings or workshops was in vain. What remains is poor information that cannot be re-used and sometimes not even found. We know about such «data graves» on shared drives, SharePoint sites, wikis or other databases. No search engine can help here anymore.

And this kind of information I call «FROZEN KNOWLEDGE».

So what can we do? Our new 3 Sphere Model links each of the steps from knowledge to information, i.e. from vapor over liquid to solid and vice versa with various knowledge management tools and techniques. A thorough professional application of these methods produces the expected benefits of knowledge management:

- Accelerated project starts

- Simpler coordination of processes

- Easier communication across organizational units (silos)

- New collaborators become productive faster

- One can find information fast as needed

What we described above was really walking alongside the 3 Sphere Model. This is how team leaders choose the right methods for innovation, communication or knowledge management. We are currently using this model in teaching and consulting as well as on the SKMF roundtables.

Knowledge Management in Project Management – Part 1: Leadership and Workshop Designs

What role does knowledge management (KM) play in project management? This was the initial question at the beginning of an initiative aimed at improving and accelerating technology and product development projects of a specific system in a large international organization. In this case the system could not be developed step-by-step over a series of agile sprints, because everything depended so strongly on each other that the complex situation had to be thoroughly thought through at the start. We started the initiative with an experiment trying out a newly developed type of KM workshop.

It was one of the windy January days at the Kreidacher Höhe above Mannheim. We have been concluding the first start-up workshop based on a new 7-step methodology. Now that the workshop was almost over, all work packages (sprints) had to be sequenced and incorporated into a final project plan.

During one and half days we have been rethinking and reworking our plans according to a new design developed by our knowledge management team. This workshop design forced us to reflect about critical knowledge gaps while simultaneously creating a matrix how to close them. The team has been also encouraged – if not forced – to think outside of the classical project methodology, as taught by PMI or IPMA. The result was that the team has recognized and defined success critical tasks outside of its traditional areas of expertise.

New level of knowledge transparency

Then came the moment to put all things together. Thanks to the level of reflection and transparency, the work sprints became much more clearer and could be placed on a much tighter time line than in the previous plan. Around the placing of the sixth or seventh sprint out of eleven somebody said that if we continued like this we would be much faster. The original plan was to reach the next milestone in November.

Knowledge management needs leadership

This is when our project leader stood up and declared to the astonished team that as we are now working with new knowledge management methodology, we have to be open to surprises. And when this means to be faster than everybody has to accept it. This came as a culture shock to some.

Thanks to this new workshop design we were able to recognize all the required measures and steps that lead to faster results. However, it took the decisive statement of our leader to actually adopt the new plan, instead of leaning back at the cushy pace following the old timetable. So finally, the milestone was moved from originally November to May, which accelerated the project by half a year.

Later on, this tangible result has lead to a broader discussion on knowledge management techniques within the company. Additional teams have also tried out the same workshop design for an accelerated project start. Additional workshop types were developed like improvement of team communication or lessons learned.

Workshop designs based on knowledge management principles

The main learning from that January team achievement was that it does not suffice to conduct just any type of a kick-off workshop. Crucial for the success of a project is the synchronized knowledge triggered and elicited through a special workshop design. Workshop design means the actual, detailed process of how the workshop is orchestrated, which tools are used and how to bring out the knowledge of the participants in order to improve thinking and reflection within and across all participants. And finally, the determination of the project leader, who ensures the implementation of the decisions.

How to survive digitalization?

There is one law of marketing that says in a fully transparent market (after a while) nobody can make money. I learned this from a Wharton School professor before the dawn of Internet. However, in our age of digitalization, this becomes a cruel reality to many business owners – a question of survival.

Coiffeurs are one type of business, which offer something you have to physically get to the shop to buy. Shops of this kind offer at the same time relationships and human touch. In contrast, products like radio, photo or other electronics are 100% comparable online. Regardless where you buy, the product is exactly the same. Therefore, shops selling those goods are loosing turnover as the customers buy at the cheapest store and mostly online. By the law mentioned above this kills any profit margins. There are still many shops like this – I call them box movers – and they will suffer, if they do not change.

Chance for survival? Find the right communication mix.

People like to meet other people and face-to-face exchange is hard to beat with online experience. A MIT study done for BMW has shown that 80% of creative ideas are generated in dialogues while people meet and talk. The power of personal communication is still unchallenged. The personnel in businesses have special know-how that can be used much broader than only for selling.

Building communities around a shared passion

To embrace the future, one has to discover new innovative approaches. It takes some reflection on the above facts and to be able to empathize well with people. Does a photography store gather photo enthusiasts in meet-ups? Does a high-end hi-fi store manage a classical music enthusiast community? Could the knowledge of the store employees be used in a new way?

There is a chance to offer services and meeting places beyond what is already there. Unfortunately, today other parties than those stores offer such courses or workshops. So there is some catching-up work to do.

A new task for PR professionals

There is a potential to build personal connections with customers. Meeting places open new opportunities for stores or any type of businesses with otherwise comparable and exchangeable products. The communication in the Instagram, Pinterest or Facebook worlds must be re-channeled and complemented with personal communication in face-to-face communities. To build up these communities could become a new task for PR professionals.

Currently, those communities are often still disconnected with classical businesses. If these companies can learn and develop into heterogeneous communication communities, they will have a chance to survive in the future.

In this sense digitalization will get rid-off simple box movers and offer new opportunities to entrepreneurs who embrace a more holistic approach to their customers. Public relations can step forward and take on a new role as community builders.

Knowledge management starts with value

Discussion around knowledge management (KM) unfortunately often center about this or that tool. What is the best tool for knowledge sharing? What is the best knowledge management system? Should we implement design thinking? Which agile method is the best?

After being for more than 20 years in the KM arena, I have seen so many discussions, which all fail to address the main point. And the main point is: What is exactly the additional value we want to get out of our efforts? Or what value we want to to get out of improved and simplified business processes, agile methods, project management etc.?

It should all really start with identifying the additional value we expect from any type of knowledge management activities. What should a change deliver?

Here are few examples of goals from completed KM projects:

1. Collaborators can identify the right experts fast in order to receive specific mentoring to reduce the mean time to repair (MTTR) of medical instruments.

2. Projects start faster and at the same time save each project members dozens of working hours and thus shorten the time to market for key products.

3. A new business model based on digitalization is developed, accepted and adding to the revenue stream.

4. Competitor intelligence work is carried out and shared easier with the sales force than before. Sales representatives increase sales due to better arguments.

5. Unstructured office documents in disorganized shares or SharePoint sites are accessed by new employees efficiently and fast saving them valuable time.

These goal examples, which were at the beginning of a KM project, led to the following solutions:

1. Creation of a digital process collaboration portal in the Intranet enabling visual access to experts, who could help.

2. Special type workshop designed for an accelerated project start-up with 5 facilitation steps engaging the project team.

3. A series of workshops each with a unique design enabling thorough capturing of knowledge during and after the workshop.

4. A unique «Mind Office Knowledge Database» supports triggering and interconnecting information inputs.

5. Advanced Search Tool combining following search methodologies: semantic, facetted, full text, taxonomy and special expressions. Even newbies could find information fast.

The key point is to clearly separate the desired value and the business need from the choice of the tool itself. The preoccupation with the tool hinders more than helps the critical thinking about the desired outcome. This is the key success factor for successful improvement initiatives. These and other success factors are the main focus of the roundtables of the Swiss Knowledge Management Forum.

The Bliss of Empty Applications

For some years now, we observe a fascinating pattern of companies and their employees jumping enthusiastically on new collaboration applications, working with them for some time and leaving them to jump on new ones.

It all started with the abolishing of shared drives. The chaos of a myriad of files in thousands of folders and subfolders was left behind and the era of Livelink, Hummingbird, Autonomy etc. started. Soon to be replaced by SharePoints. Fully motivated people started with SharePoint, but after a few years they also have created so many SharePoint sites, that the overview was lost again.

The remedy was expected from the various new versions and these came in a nice frequency: 2007, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019, 2023 and 365. But as the time went by, people realized the new SP versions would not do the job either.

A few years ago we introduced OneNote, Confluence, then Trello and later Slack. They got to a fast start and were again enthusiastically accepted. The same is just now happening in various organizations with the digital twin of Slack – Microsoft Teams.

However, also these applications meet the same fate. After one, two years of intensive usage the overview about the content gets lost and people are disillusioned. So they are searching for the next tool.

Does this phenomena has anything to do with knowledge management? I believe it does, specifically with the necessary efforts to organize information, equip it with taxonomy and structure. Only in this way, sustainability in information access is feasible.

When people start to use an application, it is empty first. As time goes by, it is filled with content. Of course, at the beginning everybody has an oversight, because our brain can keep up. The content structure is clear and one can find anything quite easily. Our brain is happy and this is the bliss of empty applications. Acceptance is here, motivation comes with it. You know it, don’t you?

You know that at the start the satisfaction of the usage is high and people are happy. However, as the amount of information rises, the oversight gets lost. And the chaos creeps in slowly. IT does not deal with that. Who should? Assistance could come from the knowledge manager, records management or the information specialist. This is a clear link to knowledge management.

So what would be needed to keep everybody happy? This is what nobody wants to hear. Namely, some type of agreed governance, some guidelines for naming, rules how to structure the information. And the discipline to do it. This takes effort and logical work. Nobody wants to do this really.

We expect somehow applications magically doing this for us automatically. And the software suppliers keep us promising they would do. But they don’t. The AI magical fairy is not yet here.

Keep on looking for the next promising «knowledge management» tool. Blissfulness is there, I promise 🙂

Digital Amnesia – The Challenge of Digital Transformation

Several years ago one of the Swiss ministries has been sued, because they have forbidden Asian business people to enter Switzerland. They could not visit a very important congress, which for them is the key business event of the year. The reason was the outbreak of an infectious epidemic in Asia. The ministry wanted to prevent infections in Switzerland.

In order to avoid financial penalties, the ministry had to provide proofs about the information flow and the state of knowledge during the critical days. The lawyers of the Asian business people asked for the level of knowledge by the hour.

In crisis situations DMS stop to work

In quiet times each document that goes in or out is recorded meticulously in a document management system. However, in a crisis situation such as this the floors of the offices start to fill up with paper, higher and higher. Meetings, decisions go so fast, that nobody cared to record what the lawyers asked for. The decisions taken were no longer reconstructable afterwards.

This experience stood at the start of a knowledge management project. The main objective was to create traceability for important decisions in an unparalleled granularity and simplicity. We have reached this goal by creating a semi-analogue and semi-digital working process.

Digital content tsunami

Looking at todays culture in many companies, I am reminded of this project. Today, there are so many tools, which allow collaborators to create a tsunami of messages, be it in Teams, Slack, Email, text messages, Twitter, Office 365, Sharepoint etc. The golden rule, that decisions should be traceable has been lost. The information that ultimately led to a decision is hidden somewhere in the digital stream.

Many companies and organizations are faced with this issue. We call this «Digital Amnesia». The thoughtless exchange of information through so many different channels leads to a dissipation. One loses the overview. And it is too expensive to restore the order afterwards through content structuring and metadata insertion. This is one of the critical points depicted by the 3 sphere model. Because the transition into quality information is hardly done, organizations are left without actionable information.

Digital amnesia has even more facets. With the introduction of every new application or change of the operating system more information and documents is at risk to get lost.

Golden rules get lost

Through digitalization we got very far from the demand, that the status of a project must be discernible from the case-file at any given time. We communicate through channels we personally prefer and nobody has the time to track the information flow. Today, Emails are sent simultaneously to many people in a star pattern. One recipient does not know if and what the others are doing or saying. One cannot reconstruct a logical step wise progress.

Relaxed leaders have creative power

Those project leaders that know and have solved this issue can be recognized. They are much more relaxed and this shows. They’ve got their job under control. And as a by-product, their case-file is leaner. Relaxed working style is freeing power for creativity and innovations. Which means more success to relaxed leaders. Those, who do not master these technique and mechanisms are permanently restless. They are hunted by the need to keep everything in their heads.

As knowledge management consultants, we should focus away from the tools and more to habits, rules and good practices how to use the tools. They should work for us at all times and not only when they are fresh and empty.

Kiss of Death for your career: Put Records Management on your business card

With these words started a highly interesting talk of a seasoned records manager executive from one of the largest pharmaceutical companies in Basel. She has substantiated her assertion with disturbing examples of two burnouts of two records management colleagues within the last three years.

This became a topic not only of that meet-up, but also of others to follow. What is going wrong here? Records management has been gaining pace as an accompanying aspect of information and document management. Records management activities include the creation, retention, maintenance, use and disposal of records. In this context, a «record» stands for content that documents results of tasks, decisions or business transactions.

Records management is supposed to guarantee the audit-proof plausibility, unchangeability, retrievability and completeness of business processes. All these goals make perfect sense. Especially, if they improve the efficacy and speed of collaboration within (virtual) teams.

This was exactly the problem that generated one of our first assignments that deserved the name of records management. Several project teams collaborating on complex research and development tasks started to be hampered by the arbitrary way they named and filed documents.

Collateral damage

The seemingly collateral tasks of naming and filing documents proved to be the main obstacle in effective work. It has reached a state that if a person, who filed a document, was present in the room, the documents could be found within a few minutes. If not, nobody could find this document.

Luckily, management recognized the seriousness of the problem and a dedicated project was initiated. After developing a specific information architecture suitable for this kind of project work and corresponding training of the engineers everybody in the department could find any documents from any project or collaborator. The usage of the system proved sustainable over the years, because to the surprise of the users, it was much easier to follow the dedicated records management rules than the formerly used arbitrary habits.

Sustainable records management

The success of this project has been repeated in the last 15 years with many other teams. One of the success factors proved to be the mutual team agreement of how collaboration is supported by document exchange. Another was the absence of complicated software tools. Instead common sense and simple rules have been applied.

This experience however, stood in contrast to the above-mentioned experience of the records management executive. So the question we discussed at our roundtables was what is wrong here? On one hand the burn-out of records managers on the other a successful implementation of records management with over the years sustainable results.

Push from outside or success from within?

Finally, our discussions in the records management community lead to the key difference between these two cases. In the first case a records manager is appointed by a central company function with the task to convince department heads to change their work and follow a set of rules. Can become a depleting task with an uncertain outcome.

In the second case, the pain comes from within and they long for a solution. If the records management solution is developed in mutual understanding of collaboration workflows and is adjusted to their needs, with simple and clear rules, then it will lead to success.

Closing the Home Office Gap

All the virtual meetings in these past few years have transferred us into another reality. As Nicole Althaus pointed out in her recent article in NZZaS, in a team call nobody can sit at the power seat of table’s end; and neither can people fade into the second row. Often the camera is turned off and people only have their voice to make their mark.The calls have changed the conversation dynamics. Interrupting somebody’s talk now seems awkward. People do more listening.

Cutting someone off has become more difficult than in a face-to-face meeting. The conversations have become more democratic. This is one of the positive outcomes of this new experience.Unfortunately, all the facets of non-verbal communication, for the most part, are missing. And yet, these are indispensable to understand the big picture to either accept or reject an idea. As Althaus points out: «The challenging flaring in the eyes of the colleague, the ironic twitching of the corner of her mouth, the inarticulate, but clearly visible contradiction or the wordless confirmation by nodding, are all visible yet implicit parts of a conversation». Soup without salt – one more time – To understand the flow of a meeting these signals are important, but are now missing. And this is exactly why the virtual experience tastes like a soup without salt.

These signals assure us when a decision has been taken. Without them the consensus behind the decision is not so clear. One leaves the meeting without the secure notion that progress has been made. Somehow one is left in a vacuum. You could say: I personally, might leave a meeting without a clear notion that we have progressed and, be left in a sort of vacuum….How to impair the creativity of your competitor?

About 15 years ago, an MIT study showed that 80% of creative ideas originate from personal face-to-face interactions. To look at it from a different perspective one could apply the handstand technique. To eradicate 80% of creative capacity, just sell your competitor some type of virtual collaboration platform and convince their creative engineers and researchers to ideate more virtually. In doing this 80% of their creative capacity has been eradicated. Goal achieved.

This is very similar to what we are currently experiencing with Covid-19 lockdown.However, in Covid-19 times we have to leave cynicism behind and reflect on how to close the communication gaps caused by mass confinement to home offices including virtual collaboration. So, what can be done? Here are three suggestions from the knowledge management toolbox: Breaking the monolithic calls.

One option is to create separate official and private parts of a call. We, as the management team, introduced this innovation in 2017 in a small global startup company. There is an informal initial time in each call to catch-up on private things. This warming up exchange increased the efficiency of the «official» business section of the call. Very soon after this exchange we realized the power of this improvement and additional sections were introduced into calls. Triggering thinking processes through individualized canvases.

Another option is to prepare the structure of the call and mirror this structure in the accompanying knowledge capturing. To improve knowledge management within the call, this mirror structure goes far beyond just copying the agenda points. It means developing an individual canvas type of minutes for particular type of meetings. This canvas includes e.g. elements like background, context, preconception or disagreements just to name a few.

This technique has proven itself already in face-to-face meetings in, for example, our betaCodex meet-ups in Zurich before the lockdown. When used correctly, it does not only facilitate knowledge capturing, it also triggers thought processes and enhances the quality of the exchange. Managing attentionIn a face-to-face meeting there are so many things happening at the same time. We see how others react and receive all these signals and process them simultaneously within the flow of the meetings. Virtual calls deprive us from this holistic experience.

To compensate for this gap assign some call participants particular roles. They have to observe e.g. argument quality, conversation logic or participation frequency. These aspects then have a particular place in the meeting canvas and everybody can see the respective contributions. The leader of the call explicitly introduces these roles at the start and hints at the remarks from time to time during the call.

These three suggestions of how to improve virtual calls have been part of the knowledge management toolbox – and SKMF roundtables – for the last 10 years. Now, thanks to the enforced home office work due to the Coronavirus, their role and place is becoming widely recognized and appreciated. I trust they will become part of new work routines in collaboration beyond the lockdown.

What is the dream of a knowledge manager?

A recent experience during a KM symposium for a global healthcare company got me thinking about what I mean by success as a knowledge manager? In this short article, I give you my conclusion and would like to hear your thoughts.

Added value through knowledge management

I started my reflections from the end. What is the end? The end is a practical, tangible result. A result that a team produces, by which it has achieved its goals: Goals that are recognized by their superiors as a major accomplishment or breakthrough. Having worked for global companies for most of my career, this often meant a scientific or technical breakthrough.

Now comes the knowledge management part. My dream was and is to personally be part of this breakthrough achieved as a direct result of applying KM methods or techniques.

Role of the embedded knowledge manager

What does it imply? It actually means engaging directly with scientists or engineers at the very moment of discovery. It means working hand-in-hand with them as an embedded consultant. And later on convincingly demonstrating that without the use of these specific KM techniques, the result could not have been achieved. Or at least not as fast and not as effective. This becomes the lesson learned for the next time.

In one our KM projects that has been summarized in a publication in 2014 we have shown the importance of the so-called dual knowledge. The success of a research project team depends primarily on two factors: its ingenuity and competence in what might be called core tasks, and its skill in dealing with the complexity of the knowledge and information generated. This means the actual subject matter and the KM techniques.

Knowledge manager as a mountain guide?

In Switzerland, the image of the embedded consultant corresponds most closely to that of the experienced mountain guide. The subject matter is the mountain tour, the KM techniques are the climbing techniques and the combination brings the team to the top. The supporting mountain guide can react instantly according to the needs of the situation and the abilities of the team, while knowing the (scientific) goal. But he reports to the leader of the climbing party.

So accompanying a team on their journey and succeeding together is my dream of a successful knowledge manager. What is yours?

Take home for knowledge managers – Active contribution to success, instead of passive support from far away:

· As a knowledge manager take personal responsibility to reach business results

· Get directly involved as embedded consultant

· Apply and teach KM techniques while doing the core tasks

· Use the 3 Sphere model for techniques actively contributing to success and value generation

Thinking hurts – let us look for an easy way out by using a tool

Well it doesn’t hurt really, but it’s exhausting. It is especially exhausting when we have to deal with multiple things at the same time. Our brain goes on a strike and we are so glad for any moment of distraction. David Rock explains in his book «Your Brain at Work» how this works. In a chapter we follow Paul, one of his characters, during the preparation of an informal lunch with a potential client. This client has heard about a successful project of Paul’s company and is interested to hear more about it. But there is only one hour for preparation before the lunch. In this hour Paul looks at some of the past projects, opens proposals and reports, Excel sheets with cost calculations and gets lost in the details. Some phone calls and emails distract him on top of that. At the end he runs out of the office unprepared and does not even find the restaurant on time.

Managing thinking is managing your focus and to relax

Rock suggests an alternative way to prepare for that business lunch talk, namely to start with a clean sheet of paper. This helps to focus on the really important things. For example to develop a structure for the discussion and recall the key points from last projects. This could include the success factors for the last clients problem analysis, the type of solution approach and reasons for choosing it or some questions to clarify the context of the prospective client. This type of preparation is simpler and much more effective. It is also more relaxing and gives a psychological security for the talk at the business lunch.

How to beat complexity

There have been many discussion about the VUCA world and many management methods have been recommended to deal with it. At first glance these management methods seem useful, because they aim at optimization and the increase of efficiency and efficacy. These methods are fundamentally based on the old ideas of Frederic W. Taylor. The principles of Taylorism are still present today: standardization and best practices, functional separation and hierarchical organization. The main principle however, the separation between supervisors, i.e. those who think, plan or steer and those who work practically on the shop floor.

More and more this separation between thinking and doing is recognized to be particularly risky in the VUCA world. However, most of our companies are still working in this old way. In large companies only few people are able to see the whole value chain and understand it from end-to-end. But to be able to react quickly to a changing environment, individual customer needs, increased competition and rapidly changing or emerging markets, this separation proves to be dangerous. How could this gap be closed? There are at least two paths to a solution.

The first one is to continue to develop tayloristic methods even further. As Niels Pfläging has shown in this essay 2012 the taylorization and intentional management of topics like quality, risk, customer satisfaction, innovation or change has increased. Methods like Lean, Kaizen, Kanban, Design Thinking, Scrum have become main stream. The expectation is that they actually help organizations to survive in the complex world.

As history repeats itself

Process management – another well known methodology – has suffered a fate that their founders have foreseen and have warned against. Regev et al. have argued in their 2016 paper that Michael Hammer and other fathers of process management never wanted to visualize individual tasks, put them into boxes, and link them by lines to workflows. Instead, they wanted to promote thinking about the whole process and to build the value explicitly into process building. Through in-depth thinking about value generation the process should be simplified and improved.

The main principle behind business process reengineering was to design the envisioned process around outcomes and value, not tasks. However, this principle was not observed by the followers. Instead until today, in process visualizations there is no explicit connection to the value for the customers or process result recipients. So by turning a holistic approach into a mechanistic technique, the main idea of process management got lost.

When investigating the writings of other key thinkers like Peter Drucker, Edwards Deming, Charles Handy or Taiichi Ohno (Toyota Way), we see the same desire on their part to improve the clarity of thinking and revolutionize the knowledge work. However, similar to the fate of ideas of Hammer regarding process management, they were not heard. Instead a new pile of optimization methods were developed and put into operation through e.g. ISO certification standards.

As Peter Senge has made clear, systemic thinking is superior to mechanistic approaches. This thinking has to be supported by collaborative and creative environments. Clarity of thinking linked with collaboration in smaller teams that have the overview and understanding of the whole value chain is needed. I was lucky to be part of teams where such foresighted ideas were implemented already in early 90’s. This was in pharma development teams like Neupogen at AMRO or later by start-up like teams at Disetronic. Later on however, these organizational innovations were abolished through various reorganizations where the new leadership did not understand the underlying benefits, logic and collaborative ecosystem. So we were put at square one.

The result was a fall back into old ways of doing things. Today, portions of the once already working system are coming back under various names and labels. Although these tools are useful, these new implementations are sketchy and mechanistic again. The creativity and innovation does not come back automatically, only because people are seated into co-working spaces or sent to mass education courses on design thinking or agile collaboration. The history repeats itself.

Thinking and responsibility evaporate

Deming, Ohno and others have warned that effective thinking cannot be frozen into tools and operating procedures, because in this process thinking inevitably stiffens and becomes ineffective. Unfortunately, their voices were not heard. Furthermore, the same happens with responsibility about the process outcome. People cannot be held responsible for failures, once they can prove that they have applied the correct standard operating procedure or best practice. So, by using certified approaches, responsibility evaporates from companies – no one can be held responsible.

What is a better way?

Pfläging and Regev are pleading to recognize the original thoughts of Hammer, Deming and others. Create smaller groups as independent cells with enough know-how to understand the whole value chain and innovative knowledge management techniques and reflective learning to bring the team work to a higher level. BMW in Munich has embedded this in their innovation process, where ambassadors assist innovator groups to work within small self-sufficient units encompassing all key functions aspects necessary for innovating a concrete product line.

As knowledge management continues to develop in the new decade and organizational innovations like betacodex take place, we see these frameworks as a viable avenue to further develop collaborative thinking that lead to true transformations. Our vision is that one day the managers will not ask what tool do I have to use, but what type of thinking and collaboration is appropriate to solve my problem.

In the Swiss Knowledge Management Forum’s roundtables we have experimented with many of these ideas and methods over the years. Success logic, serious games, knowledge cafes, communities, learning curation, co-working or thinking acceleration have been some of those topics. We have seen how thinking gains sharpness and precision once it is freed from rigid standard technologies and prescribed operations.

Artificial intelligence and the future of human intelligence

Toyota is firing robots. This headline made it last week into Tagesspiegel. Knowledge Management and AI was for a long time thought to make people redundant through harvesting and preserving knowledge in algorithms.

Apparently the wind is changing. It is a pleasure to observe when a leading automatization company such as Toyota that invented so many methods (JIT, Lean etc.) is taking a next step. According to Mitsuru Kawai, vice president of Toyota production, there are task where the robots are being again replaced by people.

«Lights out factory» is not anymore the final end. Kawai recognized that robots do not learn or improve processes. Knowledge management, knowledge improvement cannot be done with robots. It is so obvious when spoken out.

So the knowledge and human mind come into the loop again. Innovation comes from people and knowledge management processes and methods can help to get even better. Here Swiss Knowledge Management Forum comes into focus. At the SKMF roundtables new concepts are discussed and evaluated.

BIM and Knowledge Management – Overcoming the pitfalls of the 90’s

After working on several KM projects in the Architecture-Engineering-Construction (AEC) industry, I sensed the urgency for innovation in the way one coordinates design and project information and beyond this knowledge.

Today, when Building Information Models (BIM) are being adopted, the hope lies to manage not only information, but also knowledge with these systems. Creating a good structured information basis is important. The old way to do it around files, folders or SharePoint sites is hardly sufficient anymore. However, the presently narrow focus of KM in AEC companies on management of data and information is obscuring the understanding of importance of actual knowledge processes, which are essential to the success of building projects.

Classical types of KM practices have been tried in the AEC industry. Be it lessons learned, good practices, communities of practice or project closure workshops. When looking closely, the lessons learned and project closing workshops are only useful if the whole team participates. Usually, such teams are created only for the project and then dismantled. To bring them together again, at the end, is hardly feasible, as the members are already engaged somewhere else.

The knowledge has a half-life. We are human, we forget. Sometimes this half-life is one day, sometimes even shorter. If not captured immediately within the context on site, it gets lost. So the lessons learned at the end at project end would not do anyway.

Even if the knowledge capture would be done properly, the next issue is the storage, quality of information and delivery to the potential next user. This user should automatically «stumble» upon this information at time of need. Storage in some database will not do. People do not know the information exist and it stays in its grave.

The result of this is known and painful.

Mistakes are repeated. Project performance suffers. Costly changes are done in a later phase of the construction. Knowledge is lost when people retire or leave the company.

BIM – Light at the end of the tunnel?

High hopes are now put into BIM to fulfil the KM promise. BIM has proven to be very helpful for information integration in the last decade. Information on design, geometry, procurement, fabrication and construction activities are all on one place. The aggregated information together with the 3D CAD visualization simplifies communication between different subcontractors, architects, and general contractors. One can identify issues ahead of time due to simulations of the building processes step by step. The design can be also clarified through the various visualization options.

BIM serves as a single information integration platform. Information is not anymore scattered across working groups, subcontractors and craftspeople. Also the storage in the old fragmented fashion is history. In the past there have been so many formats, nomenclatures and file conventions that it was not possible to access information fast.

Is BIM also knowledge management?

Various papers have been written on the potential of BIM for knowledge management. KM is a collection of values, processes, and techniques for improving and controlling the creation, storage, reuse, evaluation, and use of experience-based knowledge and information in a particular situation or problem-solving context.

Knowledge as opposite to information is bound to people and only present in the mind of the knowledge bearer. Thought leaders in KM (Probst, Senge, Polanyi, Drucker etc.) all agree on this.

Unfortunately, most of the recent BIM papers on KM seem to follow the fallacy of the 90’s. They do not clearly state the difference between knowledge and information. Some do even try to create new definitions for explicit and tacit knowledge – as if there would be no agreed, aligned KM glossaries based on collaborative efforts of KM communities and professional organizations like SKMF.

Getting BIM out of the IT trap

To practice KM means to understand something about psychology, sociology, organization development and a pinch of information technology. The 90’s have shown us what happens, if KM is understood as information technology endeavor only. Most such projects failed – they became known as expensive databases that do not work. If BIM is thought to be another large database for storing «knowledge», building professionals are asked to feed it with «knowledge», and the emphasis is on search and other functionality, then we remain on the road to failure.

So how can we make most use of the BIM efforts? Unmistakably, BIM offers a unique opportunity to integrate formerly scattered sources and create a single point information with defined taxonomy and metadata. The work with BIM has to be enhanced with KM practices and procedures. Here a few selected examples from past projects at AHT:

- Creation of special session designs (Think Tanks) in which issues are discussed systematically and recorded instantaneously.

- Develop discussion formats for various stakeholder sessions that take place with BIM platform present and active. These formats have to be facilitated and structured. The output is documented within BIM, including decisions, arguments and responsible persons.

- Establishing of roles for topic leadership, including the responsibility to manage an ad-hoc community of practice, mentoring and learning partnerships.

- Develop a set of tools that increase efficiency and improve use of time during these sessions (think tools, good practice cards, building matrixes etc.)

- Work cycle timing to organize these sessions in an agile manner

- Leadership with a mind-set and culture to emphasize knowledge as an asset – not only information.

- Create two types of containers in BIM for information created fast (ad-hoc) and for curated validated information.

In one of the KM project for a construction company, we have identified 18 different activities how to improve knowledge sharing. Each of them falls into one of the above categories. The key is how people interact and not how they access information. It is about the techniques found on the top left part of the 3 Sphere Model.

A key success factor of any type of a KM system is the integration of these activities and tools into the daily project work. Moto is: Work smarter, not harder. It was another fallacy of the 90’s that KM was thought to be additional work on top of everything else.

It is encouraging to see that these ideas have been already considered in two recent master thesis, I had the pleasure to supervise. In one of the cases, a special BIM-Lab was established, where the BIM sessions take place. The lab has several rooms, each equipped with necessary infrastructure for knowledge cafes, small group environment, and interactive BIM projections.

This organization is on a good way to go beyond what BIM has to offer today and take a step towards a real BIM supported knowledge management. And I hope there will be many more.

Digital enthusiasm without data – An overture to New Work?

What impact will make the rush on learning and working through digital channels? I hope that it speeds up the understanding of their limits and creates the possibility to recognize their right place.

In a 2020 issue of Technology Review Nike Heinen and Natalie Wexler investigate the effects digital learning labs and Ed-tech in general have on learning results of students. While there is still a great wave of enthusiasm and investment in this direction the evidence of success remains slim at best.

On the contrary, recent scientific research shows that students using laptops, tablets or other digital devices perform worse than those learning in analog class settings. The Reboot Foundation in Paris published 2019 a comparative study showing that students using digital devices in all or almost all subjects performed one grade worse than those using paper. Another study in 2015 using data from 36 OECD nations with millions of students revealed the strong underperformance of students that used computers at school. This data is even then conclusive, when social background and demographic effects are taken into consideration.

Digital rebound has already started

Some schools and universities have already realized this. The Teacher Association in northern Germany says that digital devices will lead to more distraction and underperformance. Martin Korte, a neurologist from University of Braunschweig, explains how the deep and concentrated learning works and how digital media hinder it. He argues for rethinking their role in education. Deep learning requires the third dimension (paper, post-its, books, building kits), as our brain is stimulated more efficiently. Physical presence allows the students to engage in f2f discussions. Thus they can focus on their critical thinking, to develop best arguments, and to formulate opinions.

It feels like soup without salt

As we are currently contained in our homes due to Corona the switch to working and learning online became rapidly a reality. Much faster than we could ever imagine, we are now living in a new reality. So many people are now making first steps in remote work.

In the last few weeks teachers and professors have turned their courses into online courses. Students work and learn now from their homes. While the adoption of the technology is fast, the experience starts to show that this type of work needs specific rules and interaction. It is not sufficient to bring our old ways into the online world. In a blog written after two weeks in home office a CEO mentioned that this type of work feels like soup without salt.

If you’re in a hurry, walk slowly

This Japanese proverb should become the leading principle in these Corona times. To make online discussions and even negotiations effective, new procedures, real time capturing, and roles are needed.

This seems slower at first than our usual face to face meeting habits. However, if the Mehrabian’s 7-38-55 rule of personal communication is right, we are missing more than half of critical silent messages of nonverbal communication. These missing 55% must be now integrated into the online meetings in a targeted and planned manner.

Leadership and facilitation challenge in New Work

Similar to digital learning and education, online collaboration is facing specific challenges. They have to be recognized and met by conscious simultaneous adjuvantive tasks during online sessions. In the two last weeks, I have already seen attempts in this direction.

The know-how how to do this has been developed by the knowledge management communities in the last 10 years. However, the adoption of this type of New Work has been slow. Unfortunately, these methods have usually been confined to the theory corner instead of actually applying them.

In organizations where they have been used, however, they led to improved efficiency and quality. One such example was the creation of Expert Forums, i.e. Communities of Practice with corresponding guidelines in a global Med Tech company. There the teams collaborate across multiple sites with usually more than 6 hours time difference. The collaboration guidelines and trainings contain procedures and methods of running meetings, define the necessary roles and canvas-forms using standardized terminology and other adjuvantive tasks.

Corona accelerates better understanding

As the scientific results about the effects of digital learning continue to increase, I hope that the current experimenting with online collaboration will also accelerate our understanding of what works and what not.